Charlotte Cox and

Robert Hall,Channel Islands Investigations

BBC

BBCOur demand for water is on course to outstrip supply within 25 years, according to government forecasts. So is turning seawater into drinking water a solution for the South West?

While some countries rely on the process known as desalination, the British Isles’ only fully operational plants are in Jersey and the Isles of Scilly.

Plans for sites around the country have sparked strong resistance over cost and the environmental damage caused by toxic brine released in the process.

The government says the wheels are in motion for nine sites in England – including another in the South West, with the Environment Agency saying desalination forms “part of a diverse range of supply and demand options to secure resilient water supplies for the future”.

How can desalination help?

Desalination plants remove salt from sea or estuaries in a purifying process to provide water suitable for drinking.

Worldwide, there are more than 22,000 plants operating in 170 countries, according to research commissioned by the International Desalination and Reuse Association.

Much of the Middle East and a number of smaller countries, such as Malta, the Maldives and the Bahamas, meet nearly all of their water needs through desalination.

Corrado Sommariva, former president of the International Desalination Association, says in regions like the United Arab Emirates, desalination is a “matter of life or death” due to an arid climate, scarce natural rainfall and limited freshwater resources.

He says the UK’s rainfall and ability to move and store water, means there is no urgent need for desalination, but says it could be a good “long-term” plan to build resilience to climate change.

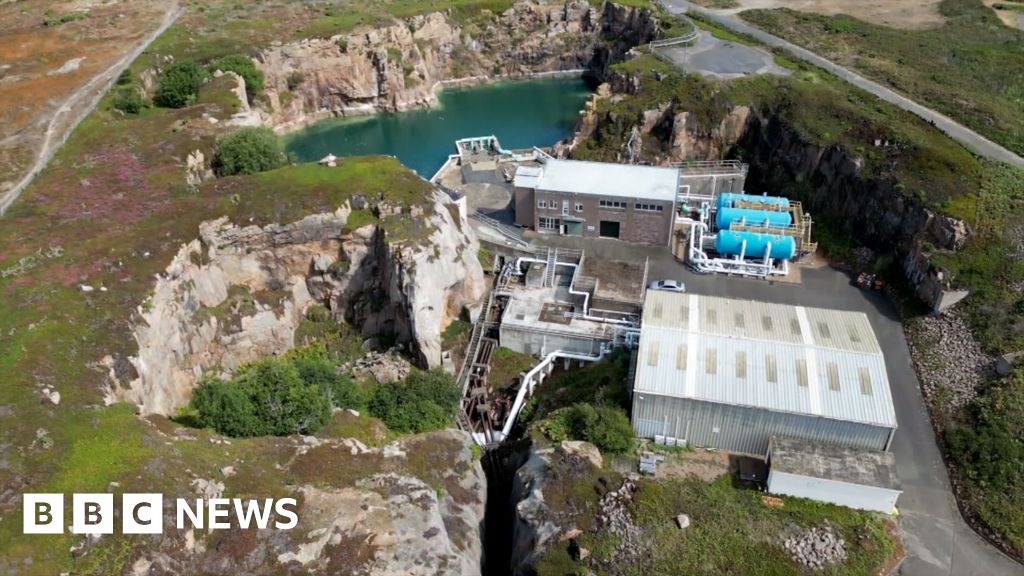

Jersey Water in the Channel Islands has been treating seawater through desalination since 1968 in response to “increasing demand and limited [water] storage”.

Jersey is entirely self-sufficient when it comes to water supply, and its reservoirs hold just 120 days’ worth of water – significantly less than anywhere in the UK, according to Jersey Water.

This means it is vulnerable to shortages in periods of low rainfall, with desalination its most “reliable, scalable and feasible” solution.

Now due a £26m upgrade, the system is expected to be used more as climate change increasingly impacts water supply, chief water operations officer Mark Manton says.

Of the plant he adds: “It is literally our lifeboat in the summer – if we get a very dry spell this is how we survive.”

Bosses took the unusual step of turning on the plant in October due to water shortages.

In the Isles of Scilly, 45km (28 miles) off the coast of Cornwall, about 40% of drinking water comes from the sea.

There was a desalination plant in Guernsey but it was closed in 1970 due to running costs.

Why don’t we have more desalination in the UK?

Up to now, there has not been a pressing need for desalination due to natural rainfall, reservoirs and the ability to move water around to where it is needed.

With climate change bringing less predictable rainfall and the growing threat of drought, this is changing, according to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra).

“Pressure on our water system is soaring, without further action demand for water will outstrip supply by 2050,” it says.

It adds £104bn of private sector investment would help to build eight new reservoirs, eight of the nine desalination plants, large-water transfer schemes and 8,000km (5,000 miles) of water mains pipes.

There are already obstacles to their construction.

A plant planned for Par in the St Austell Bay area of Cornwall has been delayed amid objections raised over concerns for marine life.

Campaigners cite concerns over pipework needed for a plant and the salt-laden brine produced in the process being pumped into the sea.

Brine raises the level of salinity and poses a risk to ocean life and marine ecosystems.

An application submitted to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) for test drilling at the Par site was rejected because it did not have “sufficient information”.

The MMO says there has been no new application submitted by SWW since that setback in February 2025.

Jenny Tagney, chair of the Friends of Par Beach group, says it will continue to “closely scrutinise” any future plans on environmental grounds.

She says evidence in favour of desalination is “not fully formed yet” to justify “the environmental devastation”.

Ms Tagney adds: “I would be really perplexed if we were to spend a lot of money, wreak a lot of havoc in nature for using it once every two years.”

Cornwall Wildlife Trust also says it will continue to hold South West Water to account.

South West Water says it remains “committed to progressing with plans to improve water resilience in the South West”, to support a growing population, summer tourism and heatwaves and droughts caused by climate change.

A plant in the South East – the only one completed outside the Isles of Scilly and Jersey – is not currently operational.

Thames Water built the £270m plant in Beckton in 2010 to provide drinking water for the capital during droughts but it has so far failed to deliver with debts and customer bills climbing.

The site is “not currently available” due to ongoing reservoir safety works at the site the plant feeds into, Thames Water says, adding it intends to operate the site in the future.

Elsewhere, more than 1,800 people signed a petition opposing plans for a plant on the shores of Southampton Water, near Fawley in Hampshire, due to concerns over the impact of brine on the environment.

What is the risk from brine?

Brine is produced when the salt is removed and it often contains other contaminants and can pose a significant threat to marine life.

A study in 2019 found much higher levels of it in the sea than previously realised, and detailed the risk to marine species from hypoxia.

Increasingly technological advances are finding new ways of mining some of the metals and salts in brine.

Mr Manton says the impact of brine at the La Rosière plant in Jersey is “minimal” thanks to the island’s unique tidal range “dispersing the brine”.

What could desalination mean for water customers’ bills?

Desalination plants are considered among the most expensive ways of creating drinking water as they pump large volumes across membranes with tiny filters at high pressure, which is an energy intensive process – and this cost is inevitably passed on to customers.

The plant in Jersey has operated for about 200 days over the last eight years, in 2018 and 2025.

In summer 2025, it ran from 15 July to mid September, costing about £180,000 in energy and manpower, Jersey Water says – although it has since been switched back on.

“It’s not an insignificant amount,” adds Mr Manton, who says the company budgets for a month of desalination a year, and accepts increasing future use could lead to higher bills.

An upgrade in 2026 is due to add 50% extra capacity to the site, from 10.8m litres a day to 16.2m.

It will cost £26m and forms part of a £48m five-year investment by JW.

Customers will be contributing to this; water bills are expected to rise on average by just under £60 from 1 January 2026, with more rises predicted for future years.

“Desalination is certainly more costly than conventional treatments because of the energy it requires,” Mr Manton says.

“You pay for the ability to mitigate the risk of running out of water.”

South West Water says it is investing £3.2bn across the group in measures including desalination – with a third of that figure to be funded by customer bills.

Average annual water bills for its customers increased by about 32% to £686 in April 2025, compared to the 26% average increase across England and Wales.

Dr Sommariva also urges caution over cost, and says desalination could offer “resilience” but is not a “golden panacea” due to higher building and energy costs in Europe compared to the Middle East.

Veolia

VeoliaWill it get cheaper and cleaner?

According to Defra, technology is being developed to deliver cleaner and more efficient desalination.

One such project is underway at the University of Manchester’s National Graphene Institute, where scientists are researching the use of graphene – the thinnest material possible and 200 times stronger than steel.

Project leader Prof Rahul Raveendran Nair says there is scope to improve energy efficiency by creating a more “durable and efficient” membrane to filter the water.

“This could also help reduce brine [waste],” he adds.

Elsewhere, Kiran Tota-Maharaj, professor of water resources management and infrastructure at the Royal Agricultural University, says: “Desalination is going to be very important to the future of water resilience and water security for the UK.”

He says the technology would be used both to convert seawater and to clean existing water reserves as they become increasingly polluted by “chemical contaminants”.

“The technology has to improve significantly across the world so that people remove that view that it’s very, very negative on the environment because of the discharge into the oceans and the seas.”

He adds: “One has to consider desalination very seriously.”